State of Change, Chapter 3: Jump-Starting the Next IT Revolution

Most of us alive today have been at the cusp of an information technology revolution for most of our careers. While we’ve thought we’ve seen at least one take place, what we’ve come to learn is that the pace of change in IT is rapid by nature. “One day you’re in,” as model Heidi Klum reminds us so fashionably, “and the next, you’re out.”

What has not changed since the 1970s is this: The people responsible for managing IT strategy remain uncertain that any strategy will yield benefits for any significant amount of time. Today, the convergence of a number of simultaneous trends has led to a situation where “the cloud” — at one time, the symbol for the indeterminate portion of the network that no one actually has to care about for it to be useful — has become the center of IT activity for businesses of all sizes. It’s a potential source for competitive advantage, and the scramble to attain that advantage while it’s still hot has earned the cloud the moniker “revolutionary.”

But if that is so — if cloud dynamics can indeed remake the corporation in a new and bolder image — then does the same fate await the cloud’s many advocates and practitioners as those who led all the IT revolutions that have come before? History is replete with revolutions, but if history repeats itself too often, they become just revolts.

Image of a horse-drawn electric tram in what was then Danzig, Germany — now Gdansk, Poland — believed to be prior to World War I, in the public domain.

The Second Shot Heard ‘Round the World: SISP 2.0

In 1991, the “SISP Revolution,” led by the advocates of Strategic Information Systems Planning, was waning. What was needed to jump-start it, some experts concluded, was another revolution.

So the leaders of SISP essentially gutted the foundation of their structural basis and started over. Gone were the polarizing notions of thrust and target put forth by Charles Wiseman in 1984, that essentially boiled down the objective for any SISP project to one good reason. Having observed that upper management has its own set of objectives and the operations department its own set, the first effort to remake SISP concentrated on balancing the two rather than choosing one.

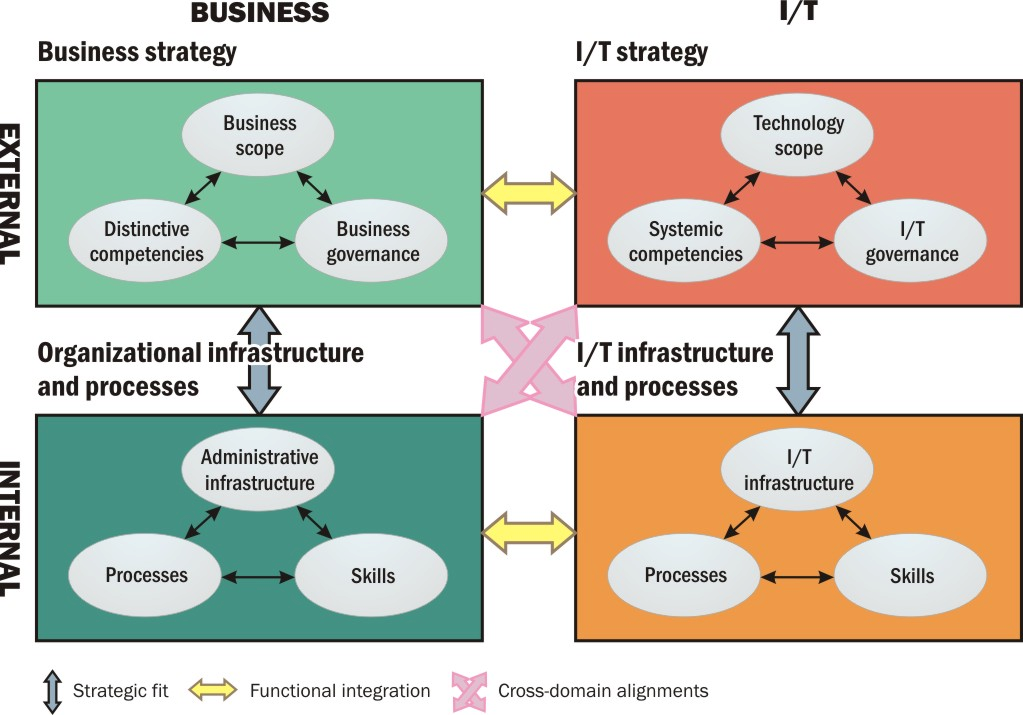

In a collection of essays from SISP leaders produced during the late 1980s and early ‘90s and eventually published in 1993 (again, publishers’ lead times), Thomas J. Allen and Michael S. Scott Morton explicitly put forth the case that the IT revolution can be intentionally and systematically engineered, rather than lit like a firecracker with a long fuse that never goes off. In one of the many essays published in Allen’s and Scott Morton’s anthology, Information Technology and the Corporation of the 1990s, N. Venkatraman re-launched his strategic alignment model, this time without the “I/S.”

Figure 3.1.

N. Venkatraman’s slightly rephrased, re-proposed strategic alignment model (1993)

The new model didn’t look much different, but it was. Whereas the first version concentrated on linkages and alignments, including the “cross-domain” variety where separate departments influence each other, Venkatraman’s new version concentrated on their distinctions and separate identities. This time, he argued that these distinctions were necessary to facilitate IT’s ability to rebuild business processes on its own, and management’s subsequent ability to follow up on that change and declare it an official strategy. He wrote:

The first feature of our model is the distinction between IT strategy and IT infrastructure and processes, and it is critical, given the general lack of consensus on what constitutes IT strategy. So, we build from the literature on business strategy, which clearly separates the external alignment (positioning the business in the external product-market space) from the internal arrangement (designing the organizational structure, processes, and systems). . . In the IT arena, given the historical predisposition to view it as a functional strategy, such a distinction had neither been made nor believed necessary. But as we consider the capability of using the emerging IT capabilities to redefine market structure characteristics as well as to reorient the attributes of competitive success, the limitation of a functional view becomes readily apparent.

Indeed, the hierarchical view of the interrelationship between business and functional strategies is increasingly being questioned, given the prevalent feeling that the subordination of functional strategies to business strategy may be too restrictive to exploit the potential sources of competitive advantage that lie at the functional level. Accordingly, functions are being considered as sources of competitive, firm-specific advantage... [In the business strategy literature], a common theme is the recognition of an external marketplace, in which these function-specific advantages can be used, and an internal organizational function, in which the functions should be managed efficiently.

The emerging view was moving away from the Synnott/Gruber inspiration of information as the static resource which a new class of executive should manage and protect. Instead, the new view was centering upon an evolving view of IT as functional, and the products of IT as dynamic elements that produced value — or, more specifically, whose intrinsic value derived from their contribution to products or services that generate revenue or lead to profitability.

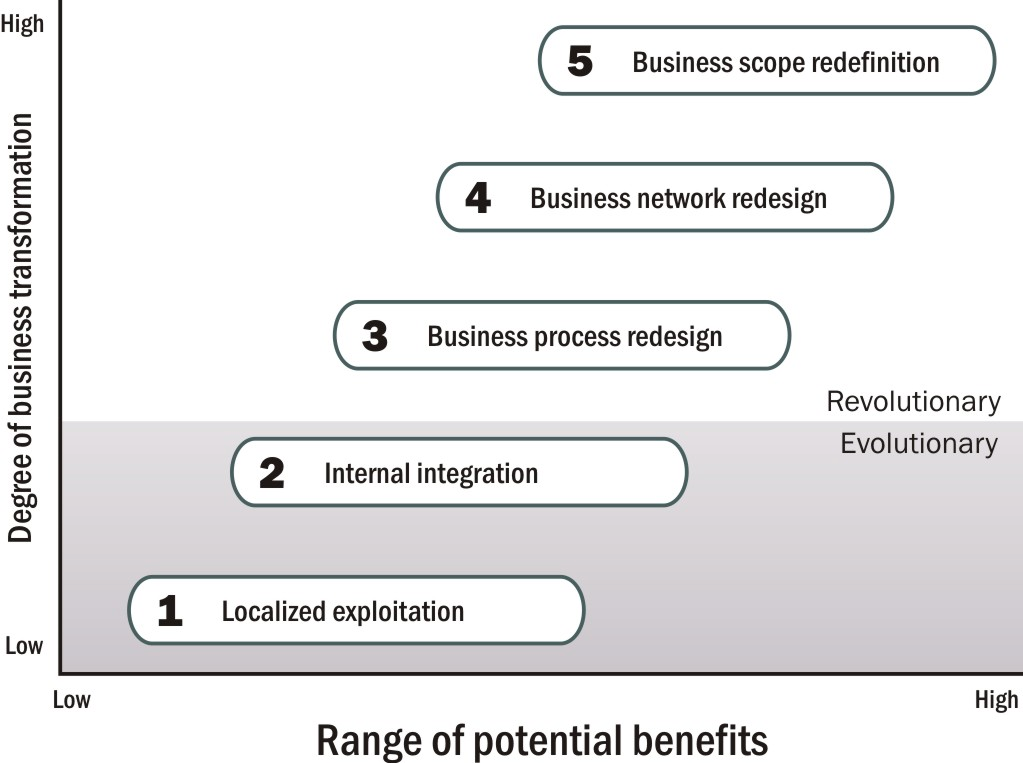

To be able to gauge when that generation would occur, and what level of generation would render these elements officially revolutionary, Scott Morton created a chart depicting five different ranges of dynamic exploitability. He called these the Five Levels of IT-Induced Reconfiguration, and others took to calling it just “The Five Levels.”

figure 3.2.

Michael S. Scott Morton’s Five Levels of IT-Induced Reconfiguration (1991)

Every IT initiative falls on one of these scales, whose horizontal breadth represents its potential for benefitting the organization. But in a stroke of genius, Scott Morton intentionally plotted the axis of benefits and the access of business transformation, or revolution, as orthogonal to one another. On the Scott Morton scale, a technology may end up being enormously beneficial, but no amount of benefit will render it revolutionary. Transformation is something entirely different, first affecting businesses at the process level, then at the network level, and finally the scope and very definition of the business itself. And that transformation, however great, is not necessarily beneficial. That may be for history to judge.

As Scott Morton projected it, all technology is beneficial to some degree, perhaps a very low one. Some other factor is required to make it revolutionary, assuming the business actually requires a revolution. Earlier, Wiseman had advised that an IT strategy can change business processes by intentionally targeting them, and the success or failure of that targeting could be measured by the degree of competitive advantage gained. Scott Morton turned that argument sideways, suggesting instead that IT strategy can always achieve some level of competitive advantage, but the degree to which the strategy is successful depends on the degree to which that advantage is reinvested in the business to achieve revolution.

That reinvestment was something Scott Morton called transaction cost — what it takes for an organization to improve utilization of resources, drive down materials prices, and improve coordination. The coordination required for organizations to even attempt these transactions, had its own coordination cost — what it takes in raw dollars to get people to exploit some of those cross-domain alignments that Venkatraman wrote about. The degree to which these costs, continued Scott Morton, may collectively yield benefits constituted a risk, which could itself be calculated in dollars. In another breakthrough, he argued that these risks could be mitigated by transforming mere coordination into something more direct and more functional: collaboration.

But for collaboration to work, SISP 2.0 needed a common thread of conversation, something all the business units could jointly recognize as important. In 1993, a team led by Warwick Business School’s Prof. Robert Galliers proposed that a common cause could be dug up from a time capsule.

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) dates back to the 1960s, its ideal being the institution of paperless document exchange between companies conducting business with one another. As Prof. Galliers perceived it, if an organization devoted itself to the cause of integrating new external data sources with its existing EDI scheme — maybe for the sake of its inventory management system, or something similarly large and prominent — then it could become inspired to get creative about the goals for that integration. And perhaps in getting creative, the IS department could — maybe even inadvertently — align its goals with those of management. Wrote Prof. Galliers:

The SISP literature... recommends a multiple or eclectic approach in order to gain comparative [sic] advantage from IT. In other words, the utilisation of IT for strategic purposes should not simply depend on existing objectives and assumptions, or on improving the efficiency of existing processes. It should also incorporate radical, creative thinking which could lead to radically changed relationships with, for example, suppliers and customers; and a reorientation of the very nature of the business itself. This paper discusses the relationship between [SISP] and EDI and suggests that SISP is an appropriate environment for organisations wishing to take a strategic approach to the implementation of EDI and to the subsequent use of EDI as an infrastructure for business process redesign...

Initially, SISP was considered to be primarily concerned with the identification of a portfolio of information systems applications and the necessary technology to support these. Although much current practice still reflects this view, there is now some evidence that organisations are seeking to provide, via SISP: new or better products/services; an environment which provides a platform for flexibility and change; [and] a means by which business processes may be reengineered in line with opportunities afforded by new IT and by changed business imperatives.

Essentially, Galliers’ idea boiled down to this: If one side of the organization concentrated on SISP and the other on EDI, however you may divvy that up, then the two methodologies could soon converge upon what he called “a single view of the future.” SISP could provide EDI with the long-range, future-centric planning that it lacked, while EDI could provide SISP with something for the IS department to busy itself puzzling over.

Sadly, Galliers wasn’t really looking over his shoulder at the oncoming revolution. The Web absolutely changed the way businesses exchange information with one another. But even up until today, the lack of an underlying principle for how business entities exchange documents, as opposed to Web servers, has led experts to conclude that EDI should play a role in at least grounding the protocol for the use of the Web in business.

The Third Shot Heard ‘Round the World: EIP

At any rate, the whole SISP+EDI get-together was interrupted by the widespread implementation of TCP/IP. Internet Protocol redrew the boundaries of IS, replacing them with the IT domains we have today. This time, both IS/IT and the executive board did become galvanized toward one common goal, or at least a set of goals with the same name: the Web portal.

Just before the turn of the century, inspired by the astounding success of the seemingly unchallenged leader in Internet resource delivery — Yahoo — businesses became dazzled by the simplicity of Web access. They compared the simple search query line to the menu maze with which users had been fumbling for decades. And they decided the goal of all integration was the accessibility of all services through a browser-based home page.

“Before we wish a cataclysm upon ourselves, and seize upon the cloud as the next ‘strategic weapon’ to that effect — to borrow Charles Wiseman’s term for the nuts and bolts of IT — we need to stop and consider the damage left behind both by successful revolutions and by failed ones.”

So they made another bold attempt to conjure an alignment between the business departments. Their plan was this: IT would undertake the task of making all corporate information accessible through an enterprise information portal (EIP). Accomplishing this would require data integration, which was certainly IT’s problem to solve. But once the solution presented itself, that same solution would incorporate new business processes and policies that would help executives reach smarter decisions, and would guide management toward the greater goals of cost reduction and inter-departmental harmony.

This strategy was first articulated in 1998 by two researchers with Merrill Lynch. Christopher Shilakes and Julie Tylman essentially asked the question, why not make a search query connect with absolutely everything in the corporate network? Their originally published definition read as follows:

Enterprise Information Portals are applications that enable companies to unlock internally and externally stored information, and provide users a single gateway to personalized information needed to make informed business decisions... an amalgamation of software applications that consolidate, manage, analyze and distribute information across and outside of an enterprise (including Business Intelligence, Content Management, Data Warehouse & Mart and Data Management applications).

In 1999, CRM magazine’s Susan Borden keyed into an incentive that perked businesses’ ears: “Having invested millions in enterprise systems such as ERP applications and intranets,” Borden wrote, “companies now realize there is still a wealth of critical business information that lies untapped. In addition, the emergence of packaged portal products... plays into the corporate desire to buy, rather than build, complex enterprise systems.”

A survey of enterprises cited by Intel during this time revealed that nine out of ten had either already deployed a corporate portal, or were planning to do so immediately. Not a company that liked to be left out, Intel took it upon itself to be the world’s model company for EIP. Its architectural model, published in 2000, looked like something a future archaeologist might mistake for a shrine to a holy deity.

Figure 3.3.

Intel’s diagram of its enterprise information portal framework. [From Intel Technology Journal, Q1 2000]

Intel’s goal was to connect to one device literally everything the corporation published about itself, for public or private consumption, with an accessibility and security model yet to be determined that even its architects conceded would be “a challenge.” Nevertheless, the concept was billed as no less than the culmination of every dream for network computing, as well as the great uniting force for modern business.

In less than two years’ time, the entire EIP market, and the momentum behind it, were declared dead by industry analyst firm Datamonitor. What happened? Nobody but nobody had caught onto the fact that the manufacturers of all those classes of software that bowed and prayed to Intel’s vision of the corporate portal, might have something to say about it. When major firms including IBM, Microsoft, and Oracle purchased nearly all the upstart EIP vendors, at first, analysts took it as validation of EIP’s grounding principle — that every bit of information in the enterprise could be opened up for public queries.

Within months, however, these new corporate parents halted EIP’s progress. Soon Datamonitor declared it would stop tracking the EIP market, instead allowing its data to be “subsumed into other enterprise software markets and forecasts.” The cause of death, declared Datamonitor, was commoditization — the hardening of the EIP market to such a degree that price points were pretty much pre-determined, and no single vendor had much wiggle room to establish for itself a little something called “competitive advantage.”

While the prospect of finally zipping up the IT and management departments into one cozy component was, at the very least, interesting, Borden’s 1999 declaration was prescient. It indicated that businesses were not engaged in the task of shaping and structuring these new portals, but rather expecting vendors to do it for them.

Shots in the Dark

There have been “interim revolutions,” if you will, since the R.I.P. was declared for EIP. You know about the move to virtualization. Indeed, most enterprise data centers today to operate on virtualized platforms, and “servers” as software are now almost divorced conceptually from the hardware “server platform.” Technically, it’s virtualization that gave rise to the technologies that underpin cloud dynamics. It’s been declared a revolution (PDF available here) that led to extraordinary gains in hardware utilization and efficiency.

But as a rallying cry for business efficiencies, virtualization by itself was underpowered, and many businesses seeking to gain competitive advantage through greater efficiencies have encountered what the industry now calls virtual stall. Typically the IT department — now declared “the albatross around the neck of business” — is blamed for instituting policies and procedures for maintaining virtual machines that users merely bypass. And it’s the bypasses that become the business’ de facto policies.

You probably also know about Agile, a project management methodology originated by businesses whose software development teams could not coalesce with their IT management teams. For many organizations today, it’s a new and still experimental method of organizing and rallying teams around simpler, more iterative, more manageable goals. The ideal here is that business processes should be redefined first, and that new methodologies for building software — and eventually, building products and services — will be crafted to fit the new definitions. And for some of those organizations, Agile works.

In cases where it doesn’t — and there’s a growing number of those — the blame is cast upon the development teams, usually for “not doing it right.” Experimenters with Agile, researchers found, find the most success when they’re able to modify and adjust the suggested Agile policies until they discover what works best for them. It’s where such experimentation is lacking, they found, that Agile usually fails. In some organizations, researchers discovered, departments will actually devise clever subterfuges to avoid the broad and frequent contact that Agile actually demands — for example, appointing “inter-departmental liaisons” to communicate with other departments, who actually have no responsibility for anything whatsoever.

Indeed, the sheer quantity of failed revolutions over the past quarter-century has triggered the birth of a unique industry segment: change management. Its stated goal is to minimize the repercussions of change throughout an organization, but its unstated purpose is often to provide departments and their people with the subterfuges and coping mechanisms necessary for them to counteract change itself, and in so doing hold on to their jobs.

I’ve lost count of how many eras there have been in information technology. At this point I suspect there have been so many in such a few years’ time that they each deserve to be re-designated “periods.” Epochs in real history are bookmarked by cataclysmic events. Before we wish a cataclysm upon ourselves, and seize upon the cloud as the next “strategic weapon” to that effect — to borrow Charles Wiseman’s term for the nuts and bolts of IT — we need to stop and consider the damage left behind both by successful revolutions and by failed ones.

Revolutionary or not, SISP did achieve significant progress. It inspired organizations for the first time to consider strategy and tactics as they applied to a field of bloodless combat, and to see IT as a business function with at least equal relevance to management. By comparison, EIP left behind a massive trail of damage. It took business leaders’ eyes off the ball, made them turn their internal functions inside-out, convinced them that everything they produced was just so many equivalent units of “content,” and made them believe their window on the world should look substantially like the home page of Google.

In the next segment of this series, we’ll compare the outlook for the cloud revolution with the aftermath of its predecessors, to see if the lessons learned in the wake of our last efforts at utopia can help us get any closer to it this time.