State of Change, Chapter 21: The Mandates for Governance, Risk, and Compliance

The very existence of a value chain in the modern economy is an indicator of how much our businesses rely upon one another. We live in a more interdependent age, where everything we produce — whether it’s durable goods, machines, constructed properties, services, or intellectual property — is an amalgam of the work contributed by a handful of partners and suppliers.

This is what distinguishes the time in which we live from the dawn of the industrial era of the mid-1800s, even more so than our use of technology. It’s the tools with which we utilize one another, and the safeguards we put in place to protect ourselves. The most important capital that any business must accrue in order to function today, is confidence. Partners, suppliers, and investors must have faith that the companies they do business with, will honor their commitments, respect their customers, and most of all, exist tomorrow. But to back up that faith, they need security.

This is what “security” has come to mean with respect to information technology — certainly from the perspective of the executive board. IT still perceives security as protection from incursion and harmful influences. Meanwhile, the newest division of many corporations is exclusively focused on the concept of governance — the controls that are put in place, the practices that are adhered to, and the values that must be publicly upheld to give other companies, and even countries, the confidence to do business with them.

“We will realize that playtime is over. The time for us to withdraw into the corner and sew virtual seeds on fictitious farm plots, will have long passed. To survive the era that faces us and our progeny, we need some mutual working arrangement, some template that points to a framework that shows us the minimum requirements we need to meet, the bar we have to clear.”

Inevitably, the IT concept of security and the governance panel or department or division’s concept, will overlap. Adherence to best practices does improve information security and reduces the chances of theft or damage — at least, theoretically. As a result, IT managers and governance managers are coming together... oftentimes in the same way that Sumo wrestlers come together.

“Cultural and business alignment — If you just fall back on a framework that’s COBIT or ISO [27001], or whatever it is, and you just hold that line, you’ll be there maybe twelve months,” declared Roger Hale, a consultant and former information security director for Brocade, in comments made at a SecureWorld conference in Indianapolis. “You have to be aligned with the business goals of the company, and you have to be embedded in their culture. You have to be one of the good guys. You can’t be that security cop.”

Alphabet Soup

In many organizations, especially publicly traded companies, the idea of governance has evolved into the department of governance, risk management, and compliance (GRC). In a few of these organizations in the U.S., the director of governance has been elevated to a C-level position: the Chief Governance Officer (CGO). But this governance role came into existence because of the heightened requirement for compliance, especially with new government regulations regarding the management of information, particularly:

The Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002 (SOX) – Intended to improve the accuracy and transparency of a company’s financial reporting and accounting, SOX instituted much stringent rules regarding how a company executes an audit of its internal controls and processes.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) – Intended to set strict standards for the exchange of personal information that may apply to health records, HIPAA ends up affecting organizations of all types whose databases may include records that, when exchanged, may at some point become part of a patient’s private medical records. Thus HIPAA compliance is becoming a model for privacy standards in industries outside of healthcare.

The Gramm-Leach Bliley Act of 1999 (GLBA) contains three key provisions governing a financial institution’s handling of its customers’ key data. One main part, called the financial privacy rule (PDF available here), prohibits institutions from exchanging customers’ private information (PII) with third parties unless and until they’ve been notified and given the option to opt out. The safeguards rule (PDF available here) applies to standards for maintaining the security and integrity of PII. And an underappreciated pretexting rule prevents PII from being obtained from financial institutions under false pretenses.

The Federal Information Security Management Act of 2002 (FISMA) – Intended to apply to how federal agencies manage all data critical to the functioning of the United States, the government has made numerous efforts (most of them unsuccessful) to extend FISMA’s provisions to companies that conduct business with the government. At any rate, FISMA has spurred some commercial companies to conduct audits that would raise their privacy controls to at least FISMA levels.

Since both public and commercial enterprises in the U.S. and abroad are impacted by the implementation of these regulations to much the same degree, industry consortia have created compliance frameworks, which include guidelines for how companies meet these specified requirements. Some of these frameworks are voluntary; others, especially for companies doing business with European interests, are compulsory.

But these frameworks have evolved into something beyond regulatory guidelines, or minimum standards. They are becoming the interfaces for businesses that share any kind of information with one another. In a world where cloud dynamics is taking effect, these interfaces become the skeletons for entire business models. Most prominent among these are:

ISO 27001, an international standard which specifies the objectives, procedures, and practices that any company must adopt before the information security functions of that company can be considered valid. Its latest update was issued on October 1, 2013.

PCI DSS was created by the payment processing industry as a standard for marshaling the exchange of cardholders’ financial data, but has matured into the baseline standard for financial institutions that conduct any kind of transaction electronically.

SSAE 16 was put into effect by the Auditing Standards Board of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants in January 2010. Effectively, the new version is the U.S. edition of international accounting framework ISAE 3402. It’s a set of guidelines for auditing and reporting the controls in place within a service organization for maintaining the integrity, confidentiality, and privacy of all information, including customer data.

COSO (named for the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations, which is a consortium of accounting interest groups) is a set of frameworks for how any business conducts fraud deterrence and risk management. Beyond a mere adherence to controls and regulations, COSO (whose latest wave of revisions took effect in 2013) steps up into the realm of ethics, compelling companies that report their financial data to shareholders and customers to make public commitments to transparency, integrity, and honesty. And yes, those commitments can be audited.

COBIT (an acronym whose precise meaning, ironically, is a matter of dispute) is a set of principles guiding how management oversees and marshals the processes of the IT department. Championed by the IT Governance Institute of ISACA, its hallmark is a single-page chart listing a boiled-down set of control objectives related to IT that are common to most organizations, coupled with signs and checkmarks designating how those objectives relate to the organization. It’s a good effort to give IT managers a snapshot of their departments and how they relate to the organization at large.

COBIT is said to have been inspired by a book by a management consultant named John Thorp first published in 1999, called The Information Paradox (entire 2007 edition e-book available for free from Fujitsu here). Thorp’s goal was to design a measurement system for attaining insight into the efficiency of an initiative, or as Thorp called it, a “program.” All programs, he believed, had a finite number of outcomes. Thus the route from the initiative to the outcome could be plotted like a flowchart, which he called the results chain, except only if the items covered in that flowchart were actually of importance. This was key for Thorp, whose personal goal was to talk managers out of using project management software. With respect to the question of ensuring that measurement systems (like COBIT, which he would inspire) would be guaranteed to provide useful guidance to managers, Thorp wrote:

The key issue is not just whether a program is being delivered on time and on budget, but whether it is delivering results. This is not an easy question to answer. Even though most business executives aren’t academics, they still require a level of proof or rigor in their thinking to be convinced that their shareholders are getting value for money. This issue goes beyond simple measurement to encompass models of how a firm makes money, or, more generally, how an organization succeeds. This is precisely what a Results Chain provides in the case of an investment program. Without such a framework you just can’t know the answers to these questions.

Consider what happens if a program is actually failing to deliver the results it promised. First of all, the project management system won’t recognize this is happening on its own, and second, it can’t tell you why, precisely, because it doesn’t incorporate any model of how projects combine to produce intermediate outcomes and benefits. What the manager needs is a measurement system with the smarts to provide the same kind of analysis of the benefits that a project management system provides in the activities and tasks. What is required is a measurement system that is designed for the program universe, not just the project world.

The process of utilizing Thorp’s measurement system to obtain useful guidance, and then apply that guidance to the implementation of policies that improve outcomes in these results chains, is what he called full cycle governance. Although the concept of governance existed before Thorp, its acceptance as a kind of principle of ethical automation, began here.

But this acceptance has not always been with open arms; for many businesses, it’s been as warmly received as taxes.

Chain Gang

The firms that underwrite businesses are tasked with managing risk, and in turn with compelling the businesses they represent to manage risk for themselves. Calculating the risk incurred when any company does business with another, involves the application of some kind of framework.

Voluntarily applying a framework is about as fun and exciting as voluntarily studying for the SAT. And rallying support for frameworks within an organization is likely to look like some behavioral conditioning program from the 1950s.

One of the people responsible for marketing the idea of governance to the employees of an organization once compared herself — in a private conversation with me — to one of the “lunch patrol” ladies in her middle school, making sure everyone consumed the substance identified as broccoli. Since few people within an organization typically volunteer for lunch patrol, the duty may fall to outside agents — the insurers, consultants, and auditors who have become professional risk managers-for-hire.

At an RSA security conference in 2012, Gartner analyst Bob Blakley — literally dressed in a Satan suit — appeared on stage with a risk management panel to warn security professionals, “Risk management is not bad. It’s evil, and it’s actually the enemy of security.” He went on to explain how risk managers, obtaining their guidance from independent auditors — which is not at all where Thorp wanted organizations to go — dictate to the organizations they serve which controls they will implement and how.

More recently, at the governance panel in Indianapolis, Darrin Reynolds, Chief Privacy Officer of advertising and marketing firm Omnicom, described this scenario from personal experience:

We’re all faced with the task of having to answer security assessment questionnaires, endless inquiries into our security posture, and everybody thinks they have a fresh, new spin on asking the same, old questions. This is where I think, [with respect to] the idea that frameworks help, if we can all pick something and agree with it, that would be great. But now we have multiple frameworks that we have to lay on top of each other.

We wanted to model our organization after the ISO [framework], because we’re international, it has a lot of breadth [and] panache, respect, and recognition. But some of our clients also bring to us strange little animals that we have to take care of as well. I had never heard of GINA — the Genetic Information Non-discrimination Act — and suddenly, one of my agencies pops up with a client, and they have to be compliant with GINA. And I’m like, “Okay, now, which framework do I fit that into? Are we appropriate to stay with ISO? Do we need to look at SOC 2 for SSAE 16? Or should we be looking at something different, head off in the COBIT direction? That’s where we started, with SOX. I think part of the struggle is, even if your effort is to minimize the work and pick a standard, there’s still a lot to choose from.

In the previous article in this series, I introduced you to Eric Chiu, president of access control services provider HyTrust. In a conversation with me, Chiu raises an even more disturbing issue with respect to cloud services in general: Any company that deploys some or all of its services on a public or hybrid cloud (and in some cases, even a private cloud that can be remotely managed) delegates some of the IT management task to a third party. This is a concept that John Thorp did not foresee, where cloud dynamics fuses different companies’ IT departments into the same mesh. How can these cloud-based departments be expected to maintain confidentiality from themselves? Says Chiu:

In the end, almost every enterprise still has a set of security, compliance, and governance requirements that they have to meet. And whether that is on systems that are being managed internally, and they have their own internal audit processes and requirements, or they’re running it in somebody else’s hosted cloud, it’s the same [requirements].

However, most cloud providers have a hard time meeting those requirements. You have two levels of requirements you have to meet: the requirements of the customer and what they do in that cloud environment, but you also have to [investigate], what’s the cloud service provider doing? What are their admins doing? Because their admins now have access and ability to manage all of their customer resources. So how do I meet audit requirements for that activity? I don’t know of any cloud provider that will provide you that level of visibility, let alone that level of control. I’ll even assert that, by the very definition of going to Amazon, you have to agree that their admins can access your systems, your data, your virtual machines, your “instances,” as Amazon calls them. So by that very nature, you are already signing away your ability to restrict that. And what implications does that have? Any cloud provider admin can now access your instances and your data. How do you guarantee that you’re showing the right level of standards of care, so you can state for a fact that that data hasn’t been breached?

Our economy is replete with interdependencies — such that the smallest events may have tremendous potential impacts on the value chain. What prevents these impacts from toppling the economy completely is that so many of them cancel each other out. Michael Porter’s original concept of the value chain depicted the way these interdependencies affect and rely upon one another. Over the course of this series, we’ve seen how information is the most critical asset an organization produces, and how the management of that information defines the viability of an enterprise.

Cloud dynamics, as I call it, is the phenomenon where technological efficiencies and other pressures compel organizations to pool their resources. In the process, they incorporate new resources and services from outside the company. The result is that organizations are trading direct control and oversight of the processes that produce what they sell, for efficiencies and quality improvements that make them more valuable to customers. Products and services may be improved, but their producers become interwoven into each other, transformed into something less than “corporations” in the original sense (literally translated, a body unto itself) and more components.

Many corporations and organizations continue to believe they must own their information, along with the assets that maintain that information, for it to be useful to them. The foundation for their beliefs is that security comes from exclusivity, because what distinguishes the value of their products to customers is, by definition, unique. It seems shameful, perhaps even unpatriotic, to challenge this notion.

The people who carry the banner of governance, often from the outside of companies looking in, have dubbed themselves the “compliance community.” Their credo is that the need for ethical business practices, catalyzed by new government regulations, mandates a new level of openness with stakeholders and shareholders. Security, from their vantage point, comes from transparency — the ability to monitor what’s going on and make adjustments. At the same time, the customers with whom business is conducted must be respected, they say, and the data which pertains to them must be treated as their personal, sacrosanct property. People have the right, they say, to their own data. Security in this respect comes from privacy. It seems shameful, perhaps even unpatriotic, to challenge either of these notions as well.

Yet these three sources of security are upheld by, to borrow a phrase from “Law & Order,” “two separate yet equally important groups:” two unique business cultures whose foundational principles, since the dawn of economics itself, fundamentally oppose one another.

Community Clash

Cloud computing (the source of my phrase) enables the kind of information processing power that companies once believed they had to own in their entirety for them to be useful, to instead be delivered as services through a utility model. It reveals that interdependencies can create efficiency, at the expense of exclusivity. The terms of these interdependencies between service providers and customers define an interface, if you will, mandating how information is to be utilized once it crosses the border that was once dubbed the “firewall.” They specify the value that partners place on each other’s vital data, and how they will handle that data on each other’s behalf.

The terms of agreement between partner companies, and between those companies and the countries in which and with which they do business, may very well become the wild cards that determine the success or failure of the modern industrial age. For these terms are metastasizing into what many perceive as constraints on business models and restraints on business strategies.

And where executives encounter restraints, they typically rebel.

“In the battle between strategy and culture, culture is going to eat strategy’s lunch every day of the week,” says Omnicom’s Darrin Reynolds.

From our corporate perspective, it’s always been very difficult to step up and tell the agencies, here’s what you’re going to do. We started to see a little of that back in 2005 with Sarbanes-Oxley. That was the first time they ever had to tell agencies, “Hey, we are publicly traded, so we need you to do X.” That was a very painful moment in their history. Since that time, we continue to grow towards centralization and consolidation, and that makes it a requirement that the company say more often, “We’re pushing policy out from the center...” But to get agencies on board with that, you have to go around and socialize that message, and it has to also feel like a grass roots development. You can’t just issue edicts from the mountaintop and expect everybody to fall in line.

You might expect IBM to have a solution in mind. Borrowing from the sudden popularity of analytics visualization tools for charting the correlations (real or imaginary) discovered amid the growing piles of big data, IBM is building out its InfoSphere big data platform to include internal auditing. The hope here is that executives’ interest in big, colorful, meaningful “dashboards” will lead to the adoption, however inadvertent, of a template for a standard set of controls that will ensure that chart is meaningful rather than a chaotic mess of circles and arrows.

David Corrigan, IBM’s director of product marketing for InfoSphere, explains his strategy in an interview:

The dashboard allows business users to get a visual context of confidence immediately, so you have knobs and dials indicating confidence level. [Perhaps] quality is at an acceptable level, but not quite there in terms of privacy. You can see this at an enterprise level; you can construct dashboards for individual application levels. So say I’m the Chief Marketing Officer, and I want to understand my confidence level, just in my data that’s running in my applications. Dashboards can be built for exactly that.

The point that we’re driving at here is, confidence can’t be invisible. It needs to be obvious to the business users, not just the IT professionals and the chief data officers. Businesspeople need to be able to see what’s been done to raise the confidence in this data, and whether they’re confident enough to act upon it. We think that’s a fundamentally important thing in big data. It’s not about making data perfect. You could argue it never was. But in the era of big data, it’s about saying, “What am I doing with it? Is the confidence level good enough to proceed? And what are the corresponding risks of not having it perfect, and making a decision?”

Corrigan raises an extremely important point: Most “big data” is, by definition, unstructured, and usually unprocessed. As I mentioned in an earlier article in this series, some of the data in a “big data” store may be presumed to exist elsewhere in the cloud or on the Web, and may never have been seen yet. It’s difficult, and perhaps impossible, to audit the controls placed on data that only virtually exists.

Lubor Ptacek is Vice President for Strategic Marketing at OpenText, which manages cloud-based BPM, enterprise information management, and digital asset management platforms. It’s this latter category that speaks to this question: In the modern data warehouse, where Hadoop and SQL Server co-exist, sometimes tenuously, it’s impossible to fulfill Thorp’s vision of measuring the right things if we don’t know what they are. In an interview, Ptacek tells me:

If users have access to everything, then that breach, if it happens, will have very severe consequences. This is where information governance comes in. First, we need to have our data in order. We need to know what we have and where we have it, and who has access to it. We need to assign the responsibilities according to their authorization, so they have only the rights to access the right information. And then we apply the usual security measures on top of that, to keep the bad guys out.

There are always two forces at play here: the force of productivity, where you want to organize your data in such a way that we can gain the greatest productivity. This natural, logical compartmentalization, based on the functional structure of the organization, may actually lend itself very well to that. The second force at play is the notion of information governance, compliance, and security... Usually from a governance point of view, that compartmentalization is an absolute nightmare. You are being sued and your data is being subpoenaed, and you are supposed to present the evidence. If it’s all over the place, good luck. It will be a very costly lawsuit. Organizations need to find the right balance between those two forces, in order to achieve what they need to achieve. From that point of view, usually the way it is run today is actually sub-optimal. Being able to transition into some kind of hybrid cloud model may actually represent opportunity to address both of these forces at the same time.

Yet let’s face facts: Executives aren’t really concerned with such existential problems as whether certain data truly or virtually exists, or whether the compartmentalization of the data warehouse conflicts with the guidelines articulated by some third party. Vendors such as IBM know from recent experience that executives are thrilled with the idea of carrying real, colorful result charts with them on their iPads, and they like to wear those charts’ diamonds and rings, to paraphrase Jim Croce, under everybody’s nose.

As we’ve seen with the latest slate of BI and analytics “dashboard” tools, executives like to leverage their easy-to-interpret graphics for their campaigns to “move the needle,” perhaps a little bit by the end of the week, perhaps more by month’s end. This concerns security consultant Roger Hale, who at SecureWorld described how executives can often act too hastily on what they think the business intelligence tells them.

What you get is the executive team saying, “What are my top 10 low-lying fruit that I can go after today?” So the challenge is, how do you hold to your framework, that you have to if you’re going to be successful and have a long-term program, at the same time that you do these shorter-term wins, which actually sets expectations and sets up the support that you need for your long-term framework?

The word that’s emerging from panels such as this is “consumable,” referring to the process of making the information that emerges from the governance process make sense in the executive mind. Hale suggests some human intervention, selecting some “easy wins” or “low-lying fruit” that executives can use to build their campaigns and build support for governance as something fun and exciting. But then tie these wins to long-term initiatives from the governance framework of choice, so their long-term nature does not detract from their feasibility or diminish their support.

Equal Time

Healthcare firm Johnson & Johnson faced all of these issues head-on. In a video co-produced with governance platform provider MetricStream in July 2012, J&J’s director of its eGRC program, Isabel Smith, told the story of how her company was led through the journey of thoroughly reinventing itself in order to achieve compliance and enable governance. (Let’s be frank: J&J didn’t exactly enter into this journey voluntarily.)

“What the compliance community asked for was an internal situational analysis,” explains Smith. “This was done through multiple interviews, working both top-down and bottom-up in the organization, to understand what was happening both from the group that was trying to regulate and make sure we were meeting our commitments, to those who had to execute in the business, and were subject to the things that were going on.” Essentially, the community needed a map of where the conflicts were happening. As Smith described, J&J discovered that — perhaps inadvertently — the overlapping governance groups that had maintained standards and practices for individual business units were actually reinforcing the divisions between those units — hardening their processes and preserving their exclusivity by narrowing the bandwidth between their respective interfaces.

The result was something Smith called “assessment fatigue” — a situation where every business unit was being audited by every other business unit, in search of the same facts. And no single audit yielded a complete picture of corporate compliance. Risk managers, governance managers, and security engineers all had competing visions of the end goals. And each group maintained its own set of fragmented, ad hoc collections of IT tools to address its own progress toward its own goals. It became a big data problem.

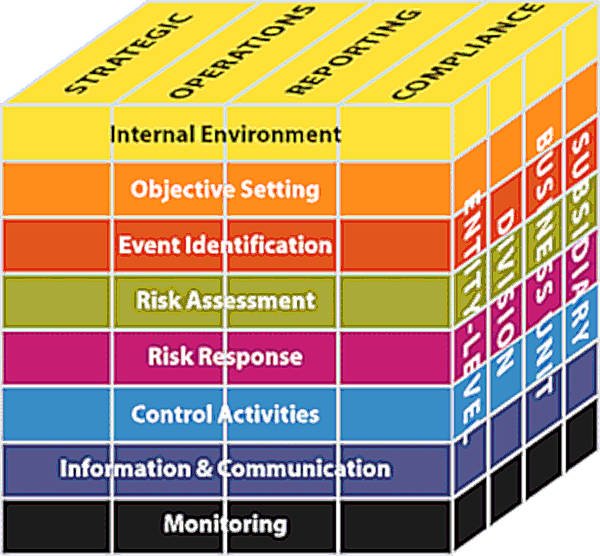

Smith then demonstrated a graphical approach to resolving these issues, utilizing a visual tool borrowed from the latest revision of the COSO Enterprise Risk Management (ERM) Framework. The chart she used is shown below. Note the curious three-dimensional aspect of this depiction. It seems that organizations are discovering the proper way to visualize their problems and map their solutions is, rather than on paper, in space.

Figure 21.1.

The COSO Risk Management Framework, devised by the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission

Though few have stepped right out and said so, the COSO ERM framework is a good effort to accept the realities in front of our face, instead of trying to mitigate them or finagle them into adjusting themselves to make our jobs easier. There are four categories of business objectives (COSO originally presented three, but Strategic was added later): strategic, operations, reporting, and compliance. Different agents with varying roles within an organization will perceive at least one objective, perhaps more, as critical. But these objectives will be different, and they will cause clashes. They just will. Notice how compliance has its own layer.

There are now eight clearly defined functions of the ERM process. They apply to everyone regardless of their roles in their organizations. While the objectives form the Z-axis of the cube, functions form the X-axis.

The Y-axis represents the subdivisions that corporations typically have, even though these subdivisions may perceive different sets of values. Whether or not they can see past their own differences, the functions of risk management must pervade them all equally.

The people in the organization with their own objectives are not made to align with one another, or coalesce, or merge. Their objectives are all equally validated.

Viewed on this model, any task which applies to the overall job of governance occupies some point inside the universe of this cube. A properly planned set of governance tasks may then be perceived on this model as an equal distribution. The goal here, as with the goal I set out for the 3D Value Chain, is not to change who people are or how they work, but rather to place them in roles and functions that achieve the greatest balance. Rather than alignment, which is not always achievable in any company that maintains multiple cultures simultaneously, this goal is what I call equilibrium.

At Last

Most of us were raised in a place where we came to respect, admire, and in select cases awe, the power of brands. We were taught to interpret a message behind each brand, a message that conveyed the integrity, conscience, and forthrightness of the vision of its founders. A brand conveyed a principle when it was stamped on an automobile, or affixed to an agreement, or emblazoned on a start-up screen. It was a signature that conveyed an ideal, which usually translated to an emblem of corporate power.

In this same place, we were raised to respect, revere, and in select cases worship, the power of countries. We were taught that certain countries represented a greater cause, a common good, a brilliant future that would surpass even the means countries undertook to secure the present.

But we live today in a world and an economy and a society where no single institution, regardless of its shape or stature, can survive for long without incorporating ideas, resources, principles, practices, and even people from other institutions. “Integrity” becomes a quality which may still describe the soul of its founders, or the memory of that soul. Yet we are now drawn together and compelled – or in some instances forced – to weave our operations, open our boundaries, and share our resources with our peers, and in so doing trade integrity (the quality of our being whole and self-contained) for prosperity.

It is not law that applies this force, or popularity or competitiveness or even wisdom. It may be mere physics. Information is the common commodity of our age, and it is so liquid and mercurial that any effort to contain it, ends up spreading it. We talk of “data at rest” and “data in motion” as if these are two distinct states of a physical object, yet we know that information — the product of data, once received by the mind — is never, at any point, at rest. It demands being exchanged to accrue value.

We would like to think that information is the new wealth, and yet the most knowledgeable people in this new society may not necessarily share in its bounty. We try to apply the principles of capitalism and socialism to the distribution and collection of information, in efforts to ensure fairness or grow the economy or simply to amass some of that wealth for ourselves. But though we seek a leader like an Adam Smith or a Karl Marx to direct us toward that end, the truth is that the tools with which we are creating this new economy and new existence for us as a people, were pretty much thrown at us like a kindergarten teacher dispensing toys. We’re expected to sort this matter out between us, and then play nicely and quietly with each other without raising a ruckus.

It took long enough, but the rise of cloud dynamics in data centers and within organizations as a whole, is the first clear signal that we students are, at last, learning to share. We may no longer exist in a society where one organization is solely responsible for the production of any item or the provision of any service, or where any one country will serve as the sole source of peace and prosperity for the planet. It may never be up to one institution to distribute wealth or encourage growth or deliver “experiences.”

But as human beings, when confronted with the enormity of all of us together, our tendency is to recede back into ourselves, to crawl back into our holes, to guard our caves, to build our silos and subdivisions, to withdraw. It is a habit most brilliantly camouflaged by our having created “social networks” and adopted new and mobile “personal devices.” Though we have built a massive communications platform, many among us tend to use it to reflect ourselves and reflect upon ourselves. Our devices may be prefixed with “i-” yet they are but the tail ends of the largest media delivery platform ever devised, whose creator will use a tiny fraction of its revenue to construct a new, O-shaped headquarters that will be seen from space. For now, we use that platform to download music and movies. And many folks who do so, call that platform “the cloud.”

The cloud will dissipate and become something tangible, because we will soon come to understand what it truly represents — not media, or even a medium, but the means by which we cope with each other and work together. Network engineers first used a cloud symbol to represent all those parts of the network that customers shouldn’t care about, the part that comes between the sender and receiver of messages. But the cloud will lift, because information refuses to remain hidden for long. We will be faced not only with the mechanism and dynamics of the cloud, but all the unresolved issues it carries with it about our responsibilities to each other, as people and as organizations and as countries. And we will realize that playtime is over. The time for us to withdraw into the corner and sew virtual seeds on fictitious farm plots, will have long passed. To survive the era that faces us and our progeny, we need some mutual working arrangement, some template that points to a framework that shows us the minimum requirements we need to meet, the bar we have to clear.

And what will that be? What governance structure will proliferate in a post-capitalist, post-socialist, post-totalitarian, post-egalitarian society? Before we are capable of comprehending this structure, we may need at least some way to gauge whether it’s working properly. We will need some polarizing, uncompromised, indisputable characteristic to guide our proverbial compass needle in the right direction – something that says, even though we don’t quite understand what’s going on, at least we’re following our conscience.

I propose equilibrium. It is, after all, the state of affairs that all physical objects and subatomic components seek in the universe, and have always sought even without a template or a framework or a governance manager. It is the unfailing indicator of a working ecosystem, a prosperous economy, a balanced universe, and a healthy psyche. When all other indicators may fail, equilibrium may attest to the fact that even chaos, spread evenly, achieves balance and promotes growth. It may be the one symbol that still works for us once “the cloud” can no longer, amid the pervasive truths, be the cloud.